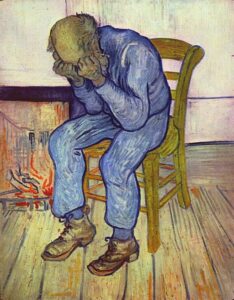

Suicide is a tragedy.

When I started writing this post, I thought that introductory sentence might be over the top. But then news organizations started publishing the following headlines:

- “Canada offered assisted suicide to a Paralympian veteran who wanted a wheelchair lift installed: report“

- “Canadian soldier suffering with PTSD offered euthanasia by Veterans Affairs“

- “Trudeau Liberals to facilitate suicide for the mentally ill starting in March

- “Canada harvests more organs from euthanized patients than any other nation in the world“

And in case you are thinking it’s just a Canadian issue:

- “America is racing toward Canada’s euthanasia free-for-all – as seven more states eye legalizing assisted suicide, deadly doses are prescribed for ANOREXICS and more nurses are inking prescriptions“

- “Yale professor under fire for suggesting elderly Japanese residents should kill themselves” (He says it was taken out of context and meant to be about aging people preventing youth from advancing. But it sure sounds like a Modest Proposal–you can hear Scrooge arguing about decreasing the surplus population. …)

And in case you think those news sources are biased, here’s the National Bureau of Economic Research:

“Deaths of despair” is the striking term researchers coined in 2015 to describe suicides, overdoses and liver disease. People who are giving up.

The reason I’m writing about this on a workplace blog is that I am dealing with deaths of despair, and people striving to avoid them, in my work. And I suspect you are too.

The research is especially clear that such deaths are happening with non-college-educated whites–but I am seeing it elsewhere as well.

What is to be done? What are your responsibilities as the manager?

Faith in the workplace

One of the frustrations expressed to me by people struggling with their mental health is this: The medications and therapy are valuable tools. But if all they do is allow someone to cope with life, there is still real pain to address below the surface. Is there any meaning to it all?

That’s the realm of religion.

“Don’t talk politics or religion.” That’s been a proverb for ages, and it’s meant to prevent heated, unproductive arguments over deeply held beliefs.

Others would argue that public expressions of faith are dangerous, stifling the rights of those with different beliefs.

I think, however, that too much is at stake to avoid the issue.

Suicide and despair involve existential pain. People in need of meaning to life.

Because of that, managers, you need to make room for faith in the workplace. Your employees will make better decisions–and it may be their only chance at overcoming choices that lead to the ultimate tragedy.

The danger of compartmentalizing

It’s common nowadays to find talking heads in the news and neighbors down the street bemoaning the lack of integrity in corporations. But that lack of integrity is not surprising.

Ethics are moral decisions, and our moral decisions are based on our beliefs. We need faith of some kind to process such beliefs and decisions.

But instead of allowing that faith, many workplaces ask employees to leave it at home.

Imagine a ship in the ocean. If part of its hull were left in the dock, it wouldn’t last as a ship for long. It has lost “hull integrity.”

When we are not “integrating” our personal and professional lives, our beliefs and our work, we can expect to sink.

The danger of unhealed wounds

Take the metaphor a step further: Imagine the ship has been under attack. Enemy fire caused the hole in the hull.

We would not expect the ship to operate without addressing such a wound. Why do we treat our people any differently?

When you imply to your team that their faith is not welcome at work, you can expect your employees to not put their full selves into their work.

They can’t. They tried to leave part of it at home.

But the wound goes untreated. And you are now employing the walking wounded.

I will tell you this is a heartbreaking part of my work: seeing people who are distracted, exploding over little things, trying to keep it all together. Once we start talking, it’s as if I’m the first person to ever listen to them and what’s going on.

That should not be.

I have been privy to conversations where the manager tells the employee that they need to figure out how to deal with it and to get back to work.

More often, though, the employee in pain is just ignored. Managers don’t know how to deal with it and don’t want to make it worse.

And that does make it worse.

Make the sacrifice

I’m not sure what your workplace needs. But here are some ideas:

Encourage rest and silence. It’s necessary, by the way, for identifying your organizational purpose. (And, as the post shares, it’s been with us since the beginning of monks creating what we now call capitalism.)

Ask your team what is the meaning in their work. Or: Ask your team what is their individual purpose. What do they want out of the job besides a paycheck?

Let me make sure it’s plain: GO TALK TO YOUR PEOPLE.

I publish this on Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, the 40 days before Easter. It’s a season of fasting as Christians prepare their hearts to celebrate the pain and death God chose to endure.

As Paul’s letter to the Philippians points out, Christ chose to empty himself and become a servant.

Good managers echo that. I’ve been a part of conversations where managers realize what is happening, or at least suspect it. They stick their neck out, sacrifice time out of their day and talk. They put their arm around the employee, pray with them, offer time off, get them help.

But it all starts with taking time to talk.

The passage in Philippians that talks about Christ emptying himself to become a servant talks about him being obedient all the way to an execution on a cross. But it also talks about how he was therefore glorified by his Father. It was worth it.

I don’t know what you’ll have to sacrifice to help your hurting people. But I think you’ll find that the sacrifice is worth it.